Based on Johnny Cash’s own autobiography and developed with considerable input from himself and his wife June up until their deaths in 2003, James Mangold (Girl, Interrupted) tells the first part of the story of a legendary life in music with astonishing power and sensitivity. Superficially, Walk the Line follows the same, tried and tested tracks of other musical biopics, but perhaps because many musicians have the same story to tell; hard times, the struggle for success and recognition, drugs, alcohol, rehab and redemption, their stories can’t help but resemble each other.

Based on Johnny Cash’s own autobiography and developed with considerable input from himself and his wife June up until their deaths in 2003, James Mangold (Girl, Interrupted) tells the first part of the story of a legendary life in music with astonishing power and sensitivity. Superficially, Walk the Line follows the same, tried and tested tracks of other musical biopics, but perhaps because many musicians have the same story to tell; hard times, the struggle for success and recognition, drugs, alcohol, rehab and redemption, their stories can’t help but resemble each other. Although JR Cash’s poor childhood in rural Arkansas is quickly told, Mangold does manage to establish three key elements of his subject’s troubled personality. We discover the impact the tragic death of his beloved older brother had on his life, that his alcoholism was likely hereditary and that his father's lifelong animosity towards him scarred him deeply. “The Devil did this,” Ray Cash (played with devastating meanness by the excellent Robert Patrick) shouts. “He took the wrong son.” And you wonder why he wore black? After a tour of duty with the Army in Germany, Cash returned to the US to marry his sweetheart Vivian (Ginnifer Goodwin), and raise their daughter. It’s just as Cash is unhappy with the direction his life has taken, and struggling to establish himself as a musician, that the film kicks into life, in an altogether rattling scene that sustains the momentum through to the finale in Fulsom Prison.

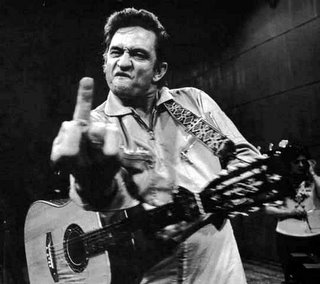

Despite being an outstanding musician, Cash was also an adulterer and an addict. To the film’s enormous credit, Mangold doesn’t pull his punches for the sake of audience sympathy. This is entirely fitting for Cash, a man who sang about his troubles and the trouble he caused so directly and so eloquently and so simply. In his autobiography, Chronicles, Bob Dylan paid homage to Johnny Cash and his music, saying that the Man in Black’s throaty growl “was so big, it made the world grow small.” In taking on that voice, and approximating the man who held it, Joaquin Phoenix delivers a startlingly good performance that never once turns into an imitation. He is note-perfect, but the film’s energy and heart come from Reese Witherspoon as June Carter Cash. She positively lights up the screen with every scene, matching Phoenix’s furrowed fervour snarl for snarl. The chemistry between them is palpable, which Mangold uses to fashion an immensely believable and compelling story. Like that startling instant, when Johnny Cash finds his voice, (“steady like a train, sharp like a razor,” as June later described it), this is a film full of riveting thumbnails; a bass guitar with the chords written on the fretboard, the first time Phoenix slings his guitar back on his shoulder, Jerry Lee Lewis’ leopard-skin collars.

Two scenes are particularly memorable, sketching the time and place with a keen eye and heart. An encounter the twice-divorced June has in a rural shop with a sharp-tongued bigot is powerfully written and brilliantly performed. Later, Cash wakes up on a tour bus and in stumbling past his sleeping guitarist Luther Perkins, plucks a cigarette out of his mouth. In real life, just months later, Perkins died in a fire in his Tennessee home, having done the same thing again.

1 comment:

You have an outstanding good and well structured site. I enjoyed browsing through it

» »

Post a Comment