Rivalling Plan 9 From Outer Space or The Sisterhood of the Travelling Pants for “Stupidest Title For A Movie”, Lucky Number Slevin isn’t the sloppily-spelled biopic of former Republic of Ireland midfielder Bernie Slavin, but a sub-Tarantino mistaken-identity crime caper from Scottish director Paul McGuigan (Wicker Park) that is ocassionally as violent and funny as you’d expect from this tired old genre, but isn’t half as clever as it thinks it is.

Rivalling Plan 9 From Outer Space or The Sisterhood of the Travelling Pants for “Stupidest Title For A Movie”, Lucky Number Slevin isn’t the sloppily-spelled biopic of former Republic of Ireland midfielder Bernie Slavin, but a sub-Tarantino mistaken-identity crime caper from Scottish director Paul McGuigan (Wicker Park) that is ocassionally as violent and funny as you’d expect from this tired old genre, but isn’t half as clever as it thinks it is. Slevin Blides Flor Slevin Blothers

Rivalling Plan 9 From Outer Space or The Sisterhood of the Travelling Pants for “Stupidest Title For A Movie”, Lucky Number Slevin isn’t the sloppily-spelled biopic of former Republic of Ireland midfielder Bernie Slavin, but a sub-Tarantino mistaken-identity crime caper from Scottish director Paul McGuigan (Wicker Park) that is ocassionally as violent and funny as you’d expect from this tired old genre, but isn’t half as clever as it thinks it is.

Rivalling Plan 9 From Outer Space or The Sisterhood of the Travelling Pants for “Stupidest Title For A Movie”, Lucky Number Slevin isn’t the sloppily-spelled biopic of former Republic of Ireland midfielder Bernie Slavin, but a sub-Tarantino mistaken-identity crime caper from Scottish director Paul McGuigan (Wicker Park) that is ocassionally as violent and funny as you’d expect from this tired old genre, but isn’t half as clever as it thinks it is. Sympathy For The Devil

Acclaimed Korean director Park Chan-wook completes his trilogy of operatic revenge films on a high note with the dreamlike Lady Vengeance. If your dreams feature dismemberment and coffee cake, that is. Following the themes of redemption and justice established in Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance and OldBoy, this time the story revolves around a young woman named Geum-ja (played by Lee Young-ae), recently released from prison having served 13 years for a notorious crime, the kidnap and murder of a young boy. The timid, religious girl that went in is a very different woman now, having spent the 13 cramped years festering in spite and plotting a complex plan. Once on the outside, she shuns her family, the rabid media attention and the creepy Christian group that helped her get parole. Using her prison contacts and keen sense of cunning, she constructs her suitably elaborate and vicious revenge, focused on one man, the evil schoolteacher Mr. Baek (Choi Min-shik from OldBoy). Reunited with her own teenage daughter, fostered in Australia, and armed with a mysterious, custom-made revolver, Geum-ja sets about her task with relish..

Flux That

Hard-won reputations take a serious kicking in Aeon Flux, with Charlize Theron following fellow Best Actress Oscar winner, Catwoman Halle Berry into the career-threatening high-wire genre of the female action superhero with similarly disastrous results.

Sometime soon, all bar five million or so of the world’s population is wiped out by a deadly virus. 400 years later, those few survivors live in a seemingly utopian society called Bregna run by Trevor Goodchild (Marton Csokas), a scientific genius who created the vaccine that saved humanity, and his brother Oren (Johnny Lee Miller). They keep a tight grip on the population via a combination of Big Brother surveillance and heavy-handed military force. The architecture all looks very high-tech, and the fashions are suitably evolved, but there is trouble in paradise and people are starting to disappear. The deadly assassin Aeon Flux (Theron) is part of a rebel group named the Monicans, led by The Handler (Frances McDormand), who have secret meetings in a courtroom inside their brains. Aeon has a sidekick, Sithandra (Sophie Okonedo), who has hands instead of feet. Hang on, I’m nearly finished. When Aeon and Sithandra are sent on a mission to kill Trevor (Trevor?), they must dodge killer grass and beehives that shoot arrows before, not unexpectedly, uncovering a vast government conspiracy and an earth-shattering secret.

A Warning From History

George Clooney's second picture as a director, the succinct and unpretentious Good Night, and Good Luck, is a modest movie, in scale, cost and running-time, but a huge film in terms of its message and relevance to today’s news media. It tells the story of a key chapter in American political life, the Communist witch hunt conducted by the paranoid, power-hungry Senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s and the efforts of television journalist Edward R. Murrow, played by David Strathrain, and his team of news producers, including Clooney as Fred Friendly, to expose him as a liar and a fraud. Murrow’s sense of decency and justice is offended by McCarthy and his cronies and in saying as much, he threatened his own position and that of his company, CBS. He is vilified by McCarthy’s supporters, his own management and by sponsors, who abandon the station as soon as the controversy breaks.

George Clooney's second picture as a director, the succinct and unpretentious Good Night, and Good Luck, is a modest movie, in scale, cost and running-time, but a huge film in terms of its message and relevance to today’s news media. It tells the story of a key chapter in American political life, the Communist witch hunt conducted by the paranoid, power-hungry Senator Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s and the efforts of television journalist Edward R. Murrow, played by David Strathrain, and his team of news producers, including Clooney as Fred Friendly, to expose him as a liar and a fraud. Murrow’s sense of decency and justice is offended by McCarthy and his cronies and in saying as much, he threatened his own position and that of his company, CBS. He is vilified by McCarthy’s supporters, his own management and by sponsors, who abandon the station as soon as the controversy breaks. In framing the meat of his story between two snippets of a brilliant cautionary speech about the importance of an independent media that Murrow delivered at a dinner in his honour, Clooney presents his key episode as an almost surgical procedure – a group of right minded people in a position to do something who fight the tide of popular opinion and commercial pressure and fear of exposure to remove a malignant presence from the body politic.

Strathrain, a renowned theatre actor and veteran of almost 80 films but still a relatively unfamiliar face, is excellent as Murrow, suave and cool on the exterior but burning with a righteous fire of indignation underneath. Clooney plays Murrow’s dedicated producer Fred Friendly, with Frank Langella, Robert Downey Jr. and Patricia Clarkson making the strongest impressions from the remainder of the large ensemble cast. The other central character is McCarthy himself, and Clooney masterstroke is having the sweaty, charmless Senator play himself, using actual archive footage to damning effect. That the movie is entirely about 50 year old politics and the early days of the American television news business might discourage Irish audiences from seeking it out. But the movie is not really about the McCarthy and his pernicious influence, rather the rightminded way in which Murrow and his team eventually engineered his downfall. Far from a bitter polemic, the film is a morality play, as relevant and important to today’s international politics and the business of reporting the truth as it is a lovingly-crafted period drama.

McCarthy's flickering presence aside, Clooney does some interesting things as a director. In shooting in glorious black & white and expending considerable energy in getting his atmosphere and production design just right, Clooney is refusing to colourise the 1950s. This isn’t ironic homage, a Technicolour trip down memory lane, its straight reportage related with a dispassionate eye and attention to detail.

The story, about tough, principled men forced by a shift in politics to make a stand, to do the hard thing in an uncertain situation, is as much a call to arms for today’s society as an opportunity to revisit the past for guidance. Clooney keeps his camera tight to create intimacy and immediacy, and his script pared down to avoid confusion. He skilfully creates an attentive calm around his key moments, provoking the audience into joining the dots between what happened 50 years ago and what is happening today in terms of press freedom and civil liberties. The film’s message is crystal clear, bullies must be stopped and liars exposed.

Heavy Jelly

A skinny black man dresses up as a fat, googley-eyed black grandmother, does a series of dirty-minded Uncle Tom skits that would have Hattie McDaniel choking on her popcorn and calls it a kid’s movie. So what? In the world of comedy, political correctness means nothing. You should be able to laugh at anybody and everybody. Anybody except Martin Lawrence.

Six years on from the character's first outing, Lawrence’s FBI agent Malcolm finds himself working undercover as a nanny for a family caught up in a murder case, an international spy-ring and a cheerleading competition. Uptight Mommy (Emily Procter) is overprotective and regimented. Absent Daddy (Mark Moses) is a boffin who’s a threat to National Security. I could try to relate the rest of the plot, but like an eye-witness to a road accident, my testimony might not make much sense after the fact. I remember there were lots of colours and loud noises. There was a dog that got drunk and one cute kid that fell down a lot and a chase scene at the beach. Big Momma shouts all the time you see, and it’s hard to stop yourself from wincing, so I might have missed a few things.

In short, entirely as you’d expect from this genre of former star relegated to ‘family’ slapsticks, the results are blatantly contrived, astonishingly vulgar and designed only to serve the Lawks-A-Mercy antics of the gurning lead.

The Irish Blog Awards

Cast a vote for me, and visit some other Irish blogs in a load of different categories at the awards website. You can go back and vote for them later...

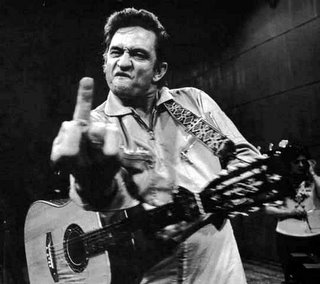

And it burns, burns, burns

Based on Johnny Cash’s own autobiography and developed with considerable input from himself and his wife June up until their deaths in 2003, James Mangold (Girl, Interrupted) tells the first part of the story of a legendary life in music with astonishing power and sensitivity. Superficially, Walk the Line follows the same, tried and tested tracks of other musical biopics, but perhaps because many musicians have the same story to tell; hard times, the struggle for success and recognition, drugs, alcohol, rehab and redemption, their stories can’t help but resemble each other.

Based on Johnny Cash’s own autobiography and developed with considerable input from himself and his wife June up until their deaths in 2003, James Mangold (Girl, Interrupted) tells the first part of the story of a legendary life in music with astonishing power and sensitivity. Superficially, Walk the Line follows the same, tried and tested tracks of other musical biopics, but perhaps because many musicians have the same story to tell; hard times, the struggle for success and recognition, drugs, alcohol, rehab and redemption, their stories can’t help but resemble each other. Although JR Cash’s poor childhood in rural Arkansas is quickly told, Mangold does manage to establish three key elements of his subject’s troubled personality. We discover the impact the tragic death of his beloved older brother had on his life, that his alcoholism was likely hereditary and that his father's lifelong animosity towards him scarred him deeply. “The Devil did this,” Ray Cash (played with devastating meanness by the excellent Robert Patrick) shouts. “He took the wrong son.” And you wonder why he wore black? After a tour of duty with the Army in Germany, Cash returned to the US to marry his sweetheart Vivian (Ginnifer Goodwin), and raise their daughter. It’s just as Cash is unhappy with the direction his life has taken, and struggling to establish himself as a musician, that the film kicks into life, in an altogether rattling scene that sustains the momentum through to the finale in Fulsom Prison.

Despite being an outstanding musician, Cash was also an adulterer and an addict. To the film’s enormous credit, Mangold doesn’t pull his punches for the sake of audience sympathy. This is entirely fitting for Cash, a man who sang about his troubles and the trouble he caused so directly and so eloquently and so simply. In his autobiography, Chronicles, Bob Dylan paid homage to Johnny Cash and his music, saying that the Man in Black’s throaty growl “was so big, it made the world grow small.” In taking on that voice, and approximating the man who held it, Joaquin Phoenix delivers a startlingly good performance that never once turns into an imitation. He is note-perfect, but the film’s energy and heart come from Reese Witherspoon as June Carter Cash. She positively lights up the screen with every scene, matching Phoenix’s furrowed fervour snarl for snarl. The chemistry between them is palpable, which Mangold uses to fashion an immensely believable and compelling story. Like that startling instant, when Johnny Cash finds his voice, (“steady like a train, sharp like a razor,” as June later described it), this is a film full of riveting thumbnails; a bass guitar with the chords written on the fretboard, the first time Phoenix slings his guitar back on his shoulder, Jerry Lee Lewis’ leopard-skin collars.

Two scenes are particularly memorable, sketching the time and place with a keen eye and heart. An encounter the twice-divorced June has in a rural shop with a sharp-tongued bigot is powerfully written and brilliantly performed. Later, Cash wakes up on a tour bus and in stumbling past his sleeping guitarist Luther Perkins, plucks a cigarette out of his mouth. In real life, just months later, Perkins died in a fire in his Tennessee home, having done the same thing again.