Breathless comic Will Ferrell plays it mostly straight in Marc Forster’s enchanting modern-day fable Stranger Than Fiction, a brilliantly realised story of an ordinary man caught up in an inexplicable fantasy.

Breathless comic Will Ferrell plays it mostly straight in Marc Forster’s enchanting modern-day fable Stranger Than Fiction, a brilliantly realised story of an ordinary man caught up in an inexplicable fantasy.

"I'm sitting in the middle of 42nd Street waiting for a bus"

Breathless comic Will Ferrell plays it mostly straight in Marc Forster’s enchanting modern-day fable Stranger Than Fiction, a brilliantly realised story of an ordinary man caught up in an inexplicable fantasy.

Breathless comic Will Ferrell plays it mostly straight in Marc Forster’s enchanting modern-day fable Stranger Than Fiction, a brilliantly realised story of an ordinary man caught up in an inexplicable fantasy.

Guillermo Del Toro’s extraordinary grown-up fairytale Pan's Labyrinth arrives on a wave of expectation, having wowed the crowd into a half-hour standing ovation at Cannes, in the process garnering the best reviews of the Mexican directors career, and it doesn’t disappoint. It is a hugely rewarding film; a rich, dark, meaty stew perfect for a long winter’s night. The story, written by del Toro, opens in Northern Spain in 1944, where we meet a young girl, Ofelia (Ivana Baquero), travelling with her pregnant mother Carmen (Ariadna Gil) from the city to the mountain headquarters of Captain Vidal (Sergi López), a Franco Nationalist on a mission to eradicate the local Republican resistance. Ofelia’s mother, recently widowed, has recently married the sadistic Captain, who has demanded she travel to the hilltop camp so his son can be born in his father’s house. Ofelia has brought her only possessions, illustrated books of fairy tales, although she has been told she is getting too old for them.

Guillermo Del Toro’s extraordinary grown-up fairytale Pan's Labyrinth arrives on a wave of expectation, having wowed the crowd into a half-hour standing ovation at Cannes, in the process garnering the best reviews of the Mexican directors career, and it doesn’t disappoint. It is a hugely rewarding film; a rich, dark, meaty stew perfect for a long winter’s night. The story, written by del Toro, opens in Northern Spain in 1944, where we meet a young girl, Ofelia (Ivana Baquero), travelling with her pregnant mother Carmen (Ariadna Gil) from the city to the mountain headquarters of Captain Vidal (Sergi López), a Franco Nationalist on a mission to eradicate the local Republican resistance. Ofelia’s mother, recently widowed, has recently married the sadistic Captain, who has demanded she travel to the hilltop camp so his son can be born in his father’s house. Ofelia has brought her only possessions, illustrated books of fairy tales, although she has been told she is getting too old for them.

Robert Altman, one of America's finest directors and a wilful, cantankerous son of a bitch, died yesterday in LA. He was 81. Like Hitchcock and Scorsese, he had been nominated for the Best Director Oscar a total of five times (the last being for Gosford Park in 2001), but never won it.

Robert Altman, one of America's finest directors and a wilful, cantankerous son of a bitch, died yesterday in LA. He was 81. Like Hitchcock and Scorsese, he had been nominated for the Best Director Oscar a total of five times (the last being for Gosford Park in 2001), but never won it. Meet the new Bond, same as the old Bond. Blonde British actor Daniel Craig might be the current incarnation of Ian Fleming’s super spy, with the filmmakers set on re-inventing the suave agent for a new generation but in Casino Royale, the much-heralded changes are mostly cosmetic. The 40 year old franchise is again produced by the Broccoli family, directed by Goldeneye’s Martin Campbell and written by veteran Bond team Neil Purvis and Robert Wade. With the success of Matt Damon’s Bourne films, Bond was forced to contemporise, but the more they change, the more things stay the same.

Meet the new Bond, same as the old Bond. Blonde British actor Daniel Craig might be the current incarnation of Ian Fleming’s super spy, with the filmmakers set on re-inventing the suave agent for a new generation but in Casino Royale, the much-heralded changes are mostly cosmetic. The 40 year old franchise is again produced by the Broccoli family, directed by Goldeneye’s Martin Campbell and written by veteran Bond team Neil Purvis and Robert Wade. With the success of Matt Damon’s Bourne films, Bond was forced to contemporise, but the more they change, the more things stay the same.  Things fall apart for Liam O’Leary, a millionaire property developer when he meets his doppelganger while stuck in a traffic jam, a sinister exact double that insidiously takes over his life in John Boorman’s snapshot of modern life in Ireland, The Tiger's Tale. Obsessed with finding out who this man is, and what he wants, O’Leary’s personal and professional lives quickly spiral out of control, as the double moves into Gleeson’s bank account, opulent mansion, boardroom and his wife’s (played by Kim Cattrall) bed. Now the Pauper to the impostor’s Prince, homeless and broke, O’Leary takes a journey of self discovery in an effort to patch up his fractured sense of identity.

Things fall apart for Liam O’Leary, a millionaire property developer when he meets his doppelganger while stuck in a traffic jam, a sinister exact double that insidiously takes over his life in John Boorman’s snapshot of modern life in Ireland, The Tiger's Tale. Obsessed with finding out who this man is, and what he wants, O’Leary’s personal and professional lives quickly spiral out of control, as the double moves into Gleeson’s bank account, opulent mansion, boardroom and his wife’s (played by Kim Cattrall) bed. Now the Pauper to the impostor’s Prince, homeless and broke, O’Leary takes a journey of self discovery in an effort to patch up his fractured sense of identity.

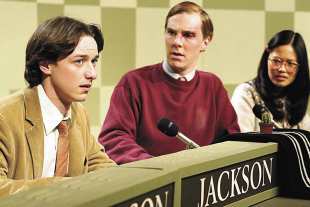

In Starter For Ten, working-class Essex-boy Brian Jackson (James McAvoy), has always been obsessed with trivia, growing up watching University Challenge on TV throughout the 70s and early 80s. When he passes his exams and gets accepted to Bristol, he leaves behind his widowed mother (Catherine Tate), and best friend Spencer (Dominic Cooper). At a fresher’s week party Brian meets the beret-wearing, right on Rebecca (Rebecca Hall, who also features in The Prestige). Just as something might happen between them, his head is turned by the snooty, stunning blonde Alice (Alice Eve), who is also his team-mate on the Bristol University Challenge squad. The story plays out against the background of the tricky TV quiz, as young Brian works out his priorities, romantic and academic, learning life lessons along the way.

Brian Kirk’s gloomy Northern Irish gothic Middletown is the story of a squat, fogbound village, marooned in what might be the 1960s, visited by an avenging angel. Fifteen years before, young Gabriel Hunter (Tyrone McKenna) is told he has been called by God for a higher purpose in life. After a spell on the African Missions, Gabriel, now played by Matthew MacFadyen, comes back to Middletown to take over the local church, with his father Bill (Gerard McSorley), brother Jim (Daniel Mays) and his wife Caroline (Eva Birthistle) waiting at a dinner in his honour.

Brian Kirk’s gloomy Northern Irish gothic Middletown is the story of a squat, fogbound village, marooned in what might be the 1960s, visited by an avenging angel. Fifteen years before, young Gabriel Hunter (Tyrone McKenna) is told he has been called by God for a higher purpose in life. After a spell on the African Missions, Gabriel, now played by Matthew MacFadyen, comes back to Middletown to take over the local church, with his father Bill (Gerard McSorley), brother Jim (Daniel Mays) and his wife Caroline (Eva Birthistle) waiting at a dinner in his honour.Daragh Carville’s screenplay begins as a drama about the chasm that exists between the ideals of a fundamentalist church and the reality of life as people live it, but ultimately wanders back to more familiar genre territory. Without some element of a personal history or any sense of humanity (even a simple mark like the ‘Love’ and ‘Hate’ etched on Robert Mitchum’s lumpy knuckles), Gabriel’s mission loses its spiritual dimension and becomes a procedural psychotic rampage. There are hints at a greater darkness, like a scene where the minister furiously scrubs his bare chest with wire-wool, but this territory isn’t explored in detail. There’s no mistaking Macfadyen’s blank-eyed conviction, whatever its source, but in the clunky melodramas that follow, he is a one-dimensional zealot, a stiff, lifeless cipher.

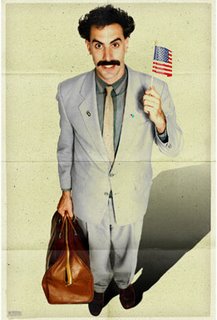

For those seven of you who don’t know, Borat Sagdiyev is the creation of British comedian Sascha Baron Cohen who, like his other alter-ego Ali G, makes the transition from small screen to big in the extravagantly, extraordinarily titled Cultural Learnings of America For Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, but for those of you who remember In Da House, this time with considerably more comic effect.

For those seven of you who don’t know, Borat Sagdiyev is the creation of British comedian Sascha Baron Cohen who, like his other alter-ego Ali G, makes the transition from small screen to big in the extravagantly, extraordinarily titled Cultural Learnings of America For Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, but for those of you who remember In Da House, this time with considerably more comic effect.Opening with a quick introduction to life in his impoverished village in impoverished Kazakhstan, proudly displaying his VCR and cassette player in the rundown shack he shares with a cow, Borat makes some quick introductions to his over-friendly sister, the fourth best prostitute in the country and his terrifying wife, who despises him, before announcing that the Ministry of Culture are to send him to make a documentary about the US and A. Enough of a storyline to satisfy our need for a consecutive narrative and sustain a stream of gags kicks in once Borat arrives in America, figures out the television in his hotel room and happens upon a rerun of Baywatch. The camera holds on his face, a picture of wonder, as Pamela Anderson bounces across the screen in slow-motion. Abandoning all other committments (the government, his journalistic integrity, the education of his nation), right there and then, Borat instead buys an ice-cream van and starts out on a road-trip, across the country to LA to find and marry the buxom babe with his flapping producer Azamat (Ken Davitian) and a huge brown bear in tow.

To further pile on the embarrassment there are a few no-holds-barred gross-out scenes. He has Western bathroom etiquette explained to him in detail by a Southern Belle and wrestles his despoiling producer naked through a crowded hotel lobby in a riotous scene, done in a single unbroken take. On the issue of anti-Semetism, Baron Cohen is Jewish, so is perfectly entitled to mine this seam for humour in the same way as, say, Tommy Tiernan casts his yellow eye on the Irish

UPDATE: Joe Queenan is a fucking idiot.

FURTHER UPDATE: Except for the opening paragraphs about Life Is Beautiful. He's bang on there, even if I don't really see the connection.