You hear him coming long before he arrives, laughing with the PR girl in the corridor, making plans for his dinner, requesting tea with sugar and braying like a donkey at whatever unheard responses she gives. She might just be the most beautiful woman I have ever seen in my life but he doesn’t seem to notice. She’s gazing up at him, eyes dancing, as he tilts his head down attentively, nodding and clapping his hands. Then the heavy door closes and, with a big grin, he bounds across the room. His handshake is firm and warm, political almost, but there’s a friendly pat on the shoulder to make you feel at ease. “Hi, I’m George”, he says, somewhat unnecessarily. Then, with a wrinkle of polite concern on his face, he asks me if I want anything. “Tea? Cuppa coffee? Too early for a drink, isn’t it? You Irish? I’m Irish.” This is old-school charm, you see, not to be confused with smarm, sincere and easy and altogether 100% Kentucky proof. A regular guy just making sure everything is comfortable and happy before getting down to business. He looks sharp, fit as a flea, groomed to perfection and smiling away, not to himself and not because there’s anything particularly amusing, but to make you smile too. It works, how could it not? It worked on the girl in the corridor. It works on everybody. I should be writing this down, I’m thinking, as moments later I have a big beam on my face and a lukewarm cup of Dorchester tea in my hand. I’m also wondering how, in the few minutes we have, George Clooney is going to explain both himself and his new movie

Syriana to me.

They say actors have two profiles, the good ones, anyway. They can turn their heads to the left or to the right and, depending on the light and the skill of the photographer, a totally different face will appear in the lens. There are, likewise, two George Clooney’s. One is the celebrity bachelor playboy; the 40-something prince of Hollywood’s new Rat Pack, a fixture in the tabloids and co-owner of a swanky Las Vegas casino. That Clooney makes disposable fluff like Ocean’s 12 and smirks at the paparazzi as he falls out of nightclubs. The other Clooney, the new Clooney, today’s Clooney, is a political philosopher agitated about the state of America, fluent in his anger and seeking to combine, somehow, the business of entertainment with a commitment to tackling social issues. The two personas appear to be diametrically opposed. So I ask him, which one is he? My reference to Las Vegas gets a grunt and a wave of his hand. He likes the other one better. “Can I be that one? The Philosopher Prince? And hey, why can’t I be both?” I tell him that, unfortunately, he needs to be pigeonholed. “I can see that”, he says, “well, first of all, the one thing I will never ever do, and you can mark my words here, is enter into politics. That is not an interesting world to me. But I do have an interest in political issues. My dad was a newsman. My mother was mayor of our home town in Kentucky. I grew up in that world and it’s been part of my whole life. But to answer your question, you can’t just come out and say ‘hey, everybody, listen to me, I’m an intellectual. I’m really smart’. Because the more you say that, the dumber you sound. So, I can’t define how people think of me. What you try to do is function as you always have and let the chips fall as they may.”

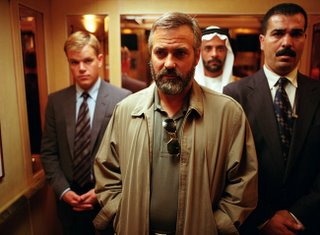

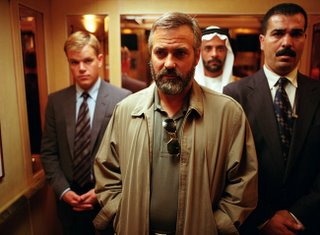

With Syriana and his own McCarthy-era broadcast journalism film Good Night, and Good Luck, Clooney has, nevertheless, positioned himself as Hollywood’s pre-eminent liberal agitator, pricking America’s conscience through his choice of films and then, wherever possible, opening up the media attention the film attracts into a discourse about the state of his country. In short, he’s worried about it. In Syriana, written and directed by Stephen Gaghan, a meandering sprawl of five separate storylines come together in a dense film that highlights America’s desperate greed for oil and the political corruption that enables that economy. Having gained 30 pounds (“ridiculously easily”) a lumbering, bearded Clooney slouches his way through the movie playing Bob Barnes, a tired and unhappy CIA agent, inspired by Bob Behr and based on his memoirs as an ‘operative’ working undercover in the Middle East, See No Evil. After assassinating two gunrunners, Barnes finds himself tasked by his superiors with killing a prominent Saudi prince who has granted gas-drilling rights to a Chinese company. Having failed in the attempt, Barnes returns to Washington where he is cut loose by his agency. Once back in Beirut, because he has nowhere else to go, the now-rogue Barnes is kidnapped and tortured. Left for dead, with no hope of return, he tries to prevent the CIA from ambushing the prince with an unmanned drone bomb. Under the advertising tag line “Everything Is Connected”, Gaghan, who penned Steven Soderbergh’s similarly wide-reaching narco-epic Traffic, tries to show us the various points of connection, a tangled, global network of corruption and greed. A businessman (played by Matt Damon) has gained influence with the ruling family of an oil-rich Gulf state and, on the other side, a US Government lawyer (played by Jeffrey Wright) becomes involved in the corruption investigation against a powerful Texan oil company over a drilling contract. In Saudi Arabia, an unemployed young Pakistani immigrant and his friend join a mosque which preaches a seductive form of jihad against the West, while deep in the background on both sides, dark forces exert their influence. It’s a thinker.

Even though Syriana has snagged a couple of Oscar nominations (for Clooney’s performance and writer/director Stephen Gaghan’s script), which should help sell it abroad, Clooney is honest about the tepid audience reaction to the film in America. “They didn’t really get it”, he says, with no apparent bitterness. “They thought it was too complicated. That’s the word I heard everywhere. Complicated. But you know what, the situation is confusing and it is complicated and as filmmakers, we can’t be afraid of that”. Clooney is certainly grateful for the stronger response in Europe, saying that we at least made an effort to understand the film. “But then”, he says, “It’s always different over here. Usually your questions have a bit of substance to them. In the US they are obsessed with the celebrity aspect of storytelling as opposed to the story itself, so its more ‘who are you dating now?’ or ‘what’s Brad Pitt really like?’ Both of which I’ll answer for you later…” There’s the booming laugh again. Sadly, I suppose, we never get back to either topic because I don’t get to ask an awful lot of questions but more because this George is interested in society, not celebrity. He wants to open people’s minds, not have them open People.

Was there a concerted effort to deal with these issues in these two films now, in particular? “I wasn’t trying to put these films together as an overall political message but at the same time, I’m not trying to separate them for you now”, he says. “The time was always right to make them and the truth is it’s totally coincidental that the two have come out so close together. Although I do think that there’s a social change going on the US where people are more interested in politics and issues again. Films naturally reflect that, but there was no conscious plan to hit the public with a one-two combination or anything”. More tea arrives. Clooney sips and is quiet for a moment. He nods his head, like he’s affirming what he’s going to say to himself before he says it. “Going back to what you said there about a change in direction for me, if you think about it, we did Three Kings back in 1998. That had a lot to say about the situation, and it was honest and forthright. Then, in 2002, in the lead up to the Second Gulf War, [the director] David O. Russell and myself tried to get it re-released in cinemas and we were told most firmly by the studio there was just no possibility of it happening. Something had changed. Now, we couldn’t make that film again, with the dialogue we had and the events we showed. We wouldn’t be allowed. My point is, it’s not just me, it’s an interesting time for filmmakers now in general and opinions are starting to get accepted again, like back in the 1970s, you know, when movies had something to say and it was OK for them to say it”.

What not acceptable, it appears, is raising debate in today’s America, especially if you’re one of the most famous celebrities on the planet. Clooney got roasted by the right-wing media when, in 2002, he criticised George W Bush and the war in Iraq. “Americans have a duty to ask questions of their government”, was his widely distributed quote. It’s a mild sentiment, more a reminder that the basis for democracy is openness and discussion than a call to arms. Nevertheless, he was branded a traitor by the neo-conservative political commentators and vilified for his work for the Democratic Party in supporting John Kerry in the last US election. Now he’s back, banging the same drum again. Didn’t he learn anything from that bad experience? “Well, first of all, it couldn’t get any worse than it was at the time in the lead-up to this war, where anyone who asked questions publicly was called unpatriotic and a traitor. I don’t fear that anymore, because it got pretty much as bad as it could get for me. I didn’t think there was any great risk to me personally, in the career sense, because our country was founded on questioning authority, although we don’t do it much anymore”. His comment lingers on the air for a moment. It seems to me like a glib generalisation, and this must have been a troubling time, so I ask him if there’s anything different about the way his message will be received today. “Well, I think the climate changed after Hurricane Katrina. The press in America for the first time took this President to task for his shortcomings”. “For the first time”, he repeats, emphasising his incredulity with a raised finger. The twinkle is gone for now. “There are a lot of moments from the years of this administration that appear laughable in retrospect. Like the Mission Accomplished photo shoot in the flight-suit on the aircraft carrier. Mission Accomplished? I mean, come on. Before then, Bush had gotten a pass because it’s perceived as being unpatriotic to go after a President during a time of war. But every other President in the history of the country had been held accountable for their mistakes and he had not. Katrina changed all that”.

Does he worry that presenting this side to the public, the boring old politics and the thinly-veiled moral lectures might be a turn-off for moviegoers, a bit of a drag? Especially when his message is filtered through the same media that Clooney is calling lazy and complicit? “No”, he says, emphatically. “The elements in the media that existed in 2003 in the lead up to the war were much more toxic than they are now. I’ve been very careful not to say ‘this is what you should believe’, but ‘this is what you should be allowed to ask’. I did it from the very beginning, and then Bill O’ Reilly [a rabid right-wing US political pundit] devotes a whole show to me, where he says my career is over because of my political views. Which, by the way, he doesn’t agree with. OK, fair enough. I can’t demand carte blanche and tell the press not to say bad things about me. I’ve got to take my hits. I’m a grown-up and I know what I’m getting myself into. But, as far as the American public goes, I’m not afraid at all because ultimately we are a pretty good country at fixing our mistakes. As I see it, we make mistakes when we attack civil liberties, when we fear talking freely and we are afraid to question authority. You go back to the beginning of our history as a country and the lesson you learn is that authority, unchecked, will be corrupt. That’s why you do it, to stave off the decay”.

This isn’t a rant. Clooney is no tub-thumper; even if he speaks very quickly, his voice is never raised and he remains perfectly composed. There’s no reason to stop him in mid-flow, so I don’t. “See, in America, we don’t know anything about foreign cultures, because we don’t have to. Before 9/11, if you asked 9 out of 10 Americans to distinguish between an Israeli and a Palestinian and, you know, point out those countries on a map, they couldn’t do it. They’d say ‘that’s all those angry guys over there in the Middle East’. Things have changed now and it’s become important for Americans to fill themselves in on the news”. But movies aren’t the news, I say. They’re movies. “Yes, but the good thing we do is to open up those regions and their stories to the public debate. The bad thing is that this sometimes leads to characterisations. It’s not my duty to speak for these nations, but it is my responsibility as a storyteller to portray people in the right way. I don’t want to do movies where the bad guys are all Arabs in headscarves brandishing AK47s. It’s a tricky situation. That’s part of the process of communicating a story to an audience. But the truth of the matter is we are saying ‘this is how the world works and these are the people that work it’. For me, our objective in the film, more than telling Bob Behr’s story, more than the oil corruption story, more than the politics, is that if you are going to have a war on terrorism, which is an idea, not a country that you can bomb, then you have to come to understand why those people do what they do. In our film we have these two young men who are attracted to the radical mosque, and at the end of the day they do something horrible. I think that watching these two young men is a step towards that understanding and the real issues behind the war. That’s the story I was interested in, much more so than the other issues, in making Syriana”.

Fuck, I say. That’s a lot of information to digest. “Yeah, well, take your time”, he says with a laugh and a grin and a twinkle and a clap on the back and you get it by now. Charm offensive maybe, but his punches are landing. “It is complicated. But I’ll say this, every time you underestimate an audience, you’ll be proved wrong. When we did the pilot for ER, years ago now, the two NBC executives there stood up and said ‘What the hell did you morons do with our three million dollars? No one understands what a ventricular arrhythmia is, why would they want to watch this?’ But my argument is that you get an impression, you get a visceral thing you can take away with you and consider later. Not everyone is going to get every twist and turn on the road here, but they’ll get it eventually”. God forbid, I say, that you might watch something unfamiliar that you might have to ask a few questions about later. “That’s the point”, he says. “That’s it exactly.” I ask him if he thinks President Bush would appreciate Syriana. “Bush? Maybe we’d have to use smaller words and lose the subtitles, but yeah, sure, he’d understand it. I don’t think necessarily that Bush is evil, by the way. I think he has a very fundamental religious belief and that he thinks he has a religious imperative to do the things that he wants to do. And that to me is dangerous in America, where we like to separate Church and State”.

We’re coming to the end of our time, and to be honest, I’m not much clearer on what Syriana is about, exactly, but to quote Roger Ebert, I’m a lot clearer on how it is about it. I’ve enjoyed talking with Clooney, he is genuinely genuine and likeable with it. He believes what he’s saying and appears at least, fearless in the face of his opponents. I’m wondering if he meant what he said about never going into politics, so I ask him if he is optimistic about the future of America? “I’m always optimistic because I believe that everything is cyclical. Going back to GN&GL, if I was around in 1954, when you had to whisper your thoughts, I would have thought that situation was an unbearably dark hole that we would never climb out of. But we did and we have since and we continue to do it constantly. When we get scared as Americans, we tend to do the stupid things that people do when they’re scared. But we pull out of it. The red witch-hunts passed, Bush will pass. We fix things and we evolve. Now the fear is that if you stick your neck out, you’ll have it cut off. I’ve had that treatment, and I survived it. Look at the times right now, where the administration says ‘we can spy on people whenever we like’, you can’t stop us and we don’t even have to tell anyone what we’re doing. Well, what’s the point of America then, what’s the union that we are protecting? You’ve got to be optimistic when you’re faced with that”.

Dying fathers battle distraught daughters in Rebecca Miller’s artfully composed and emotionally rich film about the inevitable effects of change, the passage of time and the limits of human love and idealism. More immediately, The Ballad of Jack & Rose showcases the astonishing screen acting talents of her husband, Daniel Day-Lewis and newcomer Camilla Belle in a double-act of rare power and immediacy.

Dying fathers battle distraught daughters in Rebecca Miller’s artfully composed and emotionally rich film about the inevitable effects of change, the passage of time and the limits of human love and idealism. More immediately, The Ballad of Jack & Rose showcases the astonishing screen acting talents of her husband, Daniel Day-Lewis and newcomer Camilla Belle in a double-act of rare power and immediacy.