I sat down the other day to compile my 'best of' list for the newly minted Dublin Film Critics Circle (more about that in a few weeks) and found myself surprised at how many really excellent films I saw in 2006.

I sat down the other day to compile my 'best of' list for the newly minted Dublin Film Critics Circle (more about that in a few weeks) and found myself surprised at how many really excellent films I saw in 2006.There are about 250 movies released in Irish cinemas every year. Its interesting, to me at least, that I can confidently mark 10% or so of them as being well worth watching and well-nigh essential if you consider yourself conversant with the modern cinema. Just as interesting, about 10% of that annual slate are unmitigated rubbish, leaving the majority of films in the mediocre category - that may have proved popular, like Superman Returns, Casino Royale, The Queen or World Trade Centre, but are flawed for a variety of reasons. I really enjoyed watching Superman and gave it a glowing review at the time, but the film passed from memory too quickly and my opinions on it have changed very slightly. My opinions have hardened on Casino Royale, but to a much greater extent. WTC was too bland to consider re-considering.

But the point is this. 25 movies of a standard as good as any year in the recent history of the medium is a decent rate of return for the regular cinemagoer. There are at least another 25 that won't leave you feeling disappointed, exactly. If you picked the shit 25 (to which I could add another 25 if I was feeling particularly bilious) well that's just tough.

The Departed was, for me, the most consistently entertaining and exciting film I saw this year. I am a Scorsese fan (as opposed to fanatic) but was electrified by the angular story, the gritty performances and the blank, dark tone. It's the only film this year that I went out to watch again in the cinema. So thats tops, but the remainder of the must-see list are presented in no particular order.

Best Films of 2006

United 93 - for a sense of horror that didn't fade for days

Pan’s Labyrinth - awesome visuals and brilliant writing and performances

Little Children

The New World - utterly transfixing, made me aware of changes in my breathing.

The Wind That Shakes The Barley - after The Departed, the film most people talked with me about this year

The Three Burials of Melquiandes Estrada

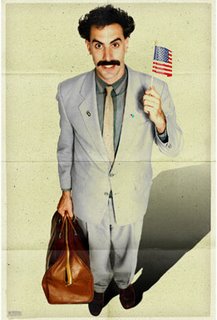

Borat: Cultural Learnings…- the funniest comedy

Red Road - the ending was disappointing, but what went before was excellent

The Host

Flags of our Fathers - angry, brilliantly realised war film

Romanzo Criminale

Crank - best action film, consistently surprising

Children of Men - most dropped jaw moments

Big Momma's House 2

RV

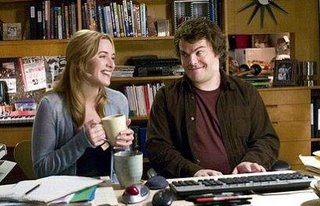

The Holiday - yikes

The Tiger’s Tale - the right things, said in the wrongest possible way

Step Up

Big Nothing

Tenacious D In The Pick Of Destiny

A Good Year - Crowe at his most crass

All The King’s Men

The Da Vinci Code - overhyped, overlong and under-entertaining

The Lady In The Water - humourless, odd, rambling junk

Life & Lyrics

Beerfest - not a single funny moment

Just My Luck - mental poison

Fast & The Furious: Tokyo Drift

Rent - distilled from the tears of unicorns

D.O.A. - beat 'em off made from a beat 'em up

The Lake House - sloppy and soppy

Rather than leave you with the thoughts of Keanu slobbering over Sandra like a stoned bloodhound eating a packet of Opal Fruits, the best film book I read this year was Patrick McGilligan's A Life In Darkness & Light (even if it was published in 2003) and the best song I heard was Mississippi Fred McDowell's [wiki] 61 Highway, which is of far earlier vintage.Man, I have to think about contemporising in 2007.