I’m laughing at a story about an actress on a short film misreading the stage direction ‘hovering’ for ‘hoovering’ when Neil Jordan pokes his head around the door and asks where he can smoke a cigarette. “Outside? Oh, Jesus”. I go with him, half wondering if I should take my recording device (I don’t) and as we smoke we talk about how the whole country got all worked up over Willie "Oh'Dear" O'Dea being photographed pointing a handgun. “What’s that all about?” asks Jordan, by way of introduction to a minor rant about the insular nature of Irish Sunday newspapers, which, according to the director, have no idea that there’s a wider world out there. “The Rocky Mountain News has more in it”.

I don’t encourage the thread of conversation simply because I don’t read Irish Sunday newspapers (or The Rocky Mountain News for that matter) and am slightly worried that if I make agreeing noises he might ask me for an example and I’d be stuck. I mutter something to the effect that the country is reeling under the weight of endless tribunals, sleazy scandals, bad politics and paranoia, and that we’re playing catch-up with ourselves. Jordan gives me a hard look, grunts, and his attention is suddenly taken by something opposite. He steps back a bit, then leans forward and peers down the side street. “Nice alley” he says and pops his butt in the ashtray on the wall. As we saunter back up the stairs, Jordan shows me an email he received that morning, claiming to be from the CIA and warning him about some hacker having gained access to his computer. Sounds like a scam, I say, although as with the Sunday papers thing, I’m edging towards the fullness of my knowledge on the subject. He calls the number at the end of the email. It is a real phone number for the actual CIA, and a computerised voice tells him that, yes, the dire warnings in the email are part of a moneymaking scam and not to do anything else but delete it. “That’s that”, says Jordan, “excitement over”.

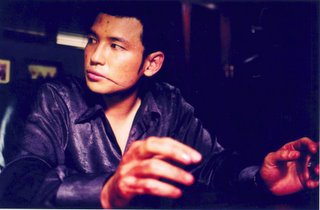

The al fresco cigarette, the ironic politician, the scam spam email and the pocket computer itself are so startlingly modern they throw the greasy scrabbling of early 1970s Ireland, when the kaleidoscopic Breakfast on Pluto is set, into sharp relief. Moving between a small country town and the bright lights of London, the Butcher Boy director’s second collaboration with Monaghan writer Patrick McCabe follows, Candide-like, the random exploits of Patrick ‘Kitten’ Braden, played by Cillian Murphy. Kitten is the result of an affair between a young woman (Eva Birthistle) and a priest (Liam Neeson), who once he's old enough, searches London for his mother and looks to make peace with his father back home. A capricious, clever and deceptively tough young transvestite, Kitten creates elaborate fantasies to escape the drudgery and pain of his isolated existence before the real escape of emigration. As Jordan gets up to close the window, I ask McCabe, who has joined us for our conversation, if he could think of another Irish filmmaker who could have taken on his novel. “No, no, it’s all too ah…too particular. There’s definitely a mood that carries from the Butcher Boy directly into this film”. I ask how they first became interested in each other’s work. “Well, we’re two Irish writers, and we’re coming off the same page in many ways”, says McCabe. Jordan pipes in, “I read The Butcher Boy basically and that was the first time I came across Pat’s work. And Pat wrote this immediately afterwards and I read it as soon as he was happy for me to see it”. McCabe comes back, saying he knew Neil’s work “for years before he had ever heard of me, ever since The Crying Game”.

Neil Jordan is just about the only pure Irish filmmaker, in that he sets out to make a different movie every time and somehow ends up saying the same things over and over again, finding new and original ways to reflect on his obsessions. Since his first film Angel in 1982 to the smash hit Crying Game in 1992 and Interview With The Vampire in 1994, he’s been inspired by childhood fairy-tales, outsiders, oblique symbolism and, ultimately, survival to redemption. Also a writer (although curiously, he has never adapted one of his own books for the screen), Jordan is enjoying a particularly juicy creative burst as he enters his mid-fifties; his new film follows 2003’s The Good Thief, producer duties on two recent Irish films, Intermission and The Actors, the publication of his fifth novel ‘Shade’ last year and the news that The Borgias, his long-delayed film about the notorious Italian family will finally go into production next year with Scarlet Johansson and Colin Farrell attached to star, although that announcement came too late for me to discuss with him. He lives in Dublin with his second wife and five children. On the day I met him he was just off the plane from the US leg of the Pluto promotional tour, had a new copy of Robert Fisk’s ‘The Great War for Civilisation’ under his arm and was wearing a speckled shirt with an interesting collar.

Patrick McCabe looks a bit like Jordan’s younger, weirder brother. Similarly stocky and direct, the Monaghan novelist and playwright is a stone-cold original with a considerable reputation. His five whirling, surreal, pop-culture books read like the 1975 Jackie annual chopped up with the Book of Revelation; featuring extraordinary, individual people in strange and uncomfortable places. They are also frequently hilarious. His 1992 book, The Butcher Boy, a black comedy narrated by a disturbed young boy in small town Ireland, was filmed by Jordan in 1996. He lives in Sligo with his wife and two daughters. Both Butcher Boy and Breakfast on Pluto were short-listed for the Booker Prize and his latest novel, Call Me the Breeze, was published in 2003. Bearded and bluff, he had no weighty tome about international relations with him that I could see, and was wearing a blue crew-neck woolly jumper.

When it came time for these two writers to write a screenplay, how did the collaboration work? “Well from his book, Pat wrote the first draft, I wrote the second and the third” says Jordan. McCabe takes a mint from a dish on the table, pops it in his mouth and says that “the film is much more Neil than me”. Both writers are at pains to explain that Breakfast on Pluto isn’t a sequel to The Butcher Boy. McCabe sees the film as fitting with a general theme in Jordan’s work. “Maybe. It’s even a bit like Angel too, if you want to go back that far, which is about innocence and the investigation of innocence and what it means when it is destroyed. You could say that The Butcher Boy is about the destruction of a child’s innocence and Breakfast is about maintaining that state of grace, regardless of what’s going on around you. If there was anything in what you’re saying, about it being seen as a sequel, it’d be something like that”. Jordan, who has been listening intently to his co-screenwriters explanation, adds that his new film and their other collaboration “if you think about it”, have more in common. “They’re both about growing up, fundamentally – childhood or adolescence in a small Irish town, yeah? They’re both, in a strange way, about characters who refuse to grow up. Butcher Boy is about Francie, who never becomes an adult (McCabe grunts his agreement, ‘oh yeah’). And I think Breakfast is about Kitten, young Patrick, who refuses to let his own innocence be destroyed, yeah? So in a way they’re both about people who refuse to grow up, with one of them ending up bloody and monstrous and the other ends up being redeemed in a way”. “Bang on”, says McCabe, sucking on his Murray Mint. “Oh yeah”, replies Jordan, “and that’s what I liked most about making this film. Everything in The Butcher Boy was edging towards darkness and apocalypse and blood, and here, the character himself transforms everything into a day-glow fairytale, and I’m not talking about fantasy or inner dreams, he actually constructs a fairy-tale around himself, it’s his solution”.

McCabe, just as stocky and square as Jordan but with a profoundly more open disposition, has a cameo in the film as Peepers Egan, a local man. I ask him if he spent much time on the set, outside of his performance. “Oh yeah, well, it’s very interesting making a movie and I love hanging around anyway. When you’re just sitting around writing stories. It gets you out of the house”. Jordan gives a big sigh. “Every writer just wants to get out of the house, you know.” McCabe agrees. “They do really, sure it drives you mad”. Out and about or not, Jordan is a notoriously difficult subject to interview. He doesn’t pretend to enjoy the process of talking about himself or his work, and seems incapable of offering pat, polished anecdotes, the familiar, pre-assembled witticisms that slip easily into a comfortable celebrity puff-piece. He thinks before he answers questions, often falling into silence, or disagreeing, or answering a question with another question. He’s not difficult or obstreperous; he’s precise, which can be just as maddening. I ask them both about dealing with the IRA in their work, looking at Jordan’s seeming obsession with the North and citing the obvious points of connection in the director’s own back catalogue. Jordan claims he doesn’t understand what I mean, so I explain further, saying that someone from the outside looking in would find it difficult to differentiate between say, Jordan’s IRA pub-bombing and the psychological weight that carries here and a pyrotechnic sequence in a Bruce Willis action movie? It’s not meant as an explicit criticism, but it sounds like one, and a clumsy one at that. Jordan just looks at me. McCabe answers, gently, saying that the IRA is at the heart of the film. “How would you deal with a young kid living on the border in 1971 without having the IRA involved? How would you do that? Given the subject matter in the film, we couldn’t avoid it”. But, I say, Jordan has gone over this ground again and again. What elements of the North, for both writers, add up to make a drama? “Well, yeah”, Jordan replies, after a silence. “I made a movie about Michael Collins, I made The Crying Game and Angel, but one of the reasons I put off making Breakfast on Pluto for so long is that I didn’t want to deal with the issue of political violence immediately again”. “Well”, says McCabe, “I can see how this would be much more of a problem for Neil than it is for me. I haven’t dealt with the IRA before in my work. The book is set in the borderland in the 1970s, so like I said, it’s unavoidable. But the quintessential IRA movie, outside of Michael Collins, simply hasn’t been made yet. It’s like a movie you’d make about Sarajevo in the nineties, like a Battle of Algiers or something. But that’s for someone else to make and write. I don’t have that kind of mind, and maybe that’s the movie you want to see, but this film doesn’t purport to deal with those issues. The IRA in the context here represents a threatening, sinister, outside force, like a pack of wolves. A film dealing directly with the IRA and covert forces in NI would be far more politically complex than what we’ve done here”.

One thing that’s fascinating about the strange world of Breakfast on Pluto is that things are never spelled out in black or white. Everybody is ephemeral, socially, sexually, politically; a turbulent ensemble cast of characters that are all open to interpretation while resisting any neat categorisation. McCabe sucks his mint, meditatively. “It prefigures the modern world, I think. Someone was saying to me, I think it was Gavin Friday (who plays showband leader Billy Rock), that a lot of the characters are people that you just didn’t see in fiction in Ireland, even if they were right there in front of everyone. They just weren’t part of the dramatic landscape, they were swept under the carpet. Now, in the modern world, we can address them because all these things are all out in the open. They had a peculiar kind of ambience feeling about them – because of it being the early seventies, where there was a lot of depression, really, and alienation and silence. So the period that it’s set in is very significant”. He’s warming to the theme, and stretches out in his chair as he expands. “The seventies were such a weird time, really. Just looking at something like ‘Reeling in the Years’ (the archive show from RTE), it seems to me now that fashionwise, politics wise and socially wise, it was all very strange and you’d find yourself wondering what were we all thinking, watching it now”. It’s like a different planet, I say, cheerfully alluding to the Pluto of the title. A bus roars by outside. McCabe sucks his mint and Jordan sucks his lemon. I use the resulting silence to ask another question.

The film’s simple chaptered structure hides a complicated, constantly shifting mood of alternating light and dark. His voyage of self-discovery leads Kitten through an ambivalent landscape, being at times light and playful and at other times heartbreakingly violent and grim. “Well, that’s what I wanted to do, so yeah, that the way it is”, says Jordan, hardly impressed with my indelicate reading. McCabe jumps in, saying “you always get that when people are talking about the troubles in the North. It’s either laughter or disaster, like. Excessive sentiment mixed with hilarity”. Jordan interrupts. “Well, talking about the politics of this film, I never thought that I’d be in Crumlin Road Jail shooting a scene for a movie that involves a bomb-making factory and a guy in PVC leather who waltzes in and annihilates everybody with a perfume spray. I just didn’t ever think I’d be allowed to do that in Crumlin Road jail, you know what I mean? It really was interesting making this film because that issue is out of bounds, it’s…dead in Irish life now. You cannot”. He stops to correct himself. “I don’t mean dead dead but it’s gone somewhere different and now its part of the past. So that was one of the things I found refreshing about the film was the central character’s attitude was so irreverent and so…clear, in a way. Kitten expresses such irreverence for traditional Irish pieties, you know? Whether it’s Nationalism or the Catholic Church or the glamorisation of what they call ‘men of violence’ and all that sort of stuff. There’s no better de-glamoriser than Kitten, really. That’s what, well, that’s why I decided to make the movie in the end, because the central character puts all that shit in its place”. It’s the most Jordan has said since he got off the phone from the CIA half an hour ago and there’s a beat while myself and McCabe absorb it. I wish I had a mint to suck on.

I ask McCabe about the kind of women he had in mind when he sat down to write them in the first place. “It was Dusty Springfield I was most thinking of”, he says, “and at that time I was playing her music over and over again”. Not seeing the connection immediately, I ask him to explain, which he does, rather randomly. “Actually, I think that where I was coming from was perhaps Denis Nielsen, you know, the serial killer. When I went to London first in the seventies this guy was running riot and a lot of the boys he killed were Irish, who were never reported or recorded. At that time, London was a very strange place and you could easily end up on the streets. I remember a guy saying to me, ‘You know you could make a lot of money flogging your arse down Piccadilly’, you know. Jordan pipes in, “You know some guy said that to me too”. He repeats a line from his movie, in a sleazy English accent, “A young Irish lad can make a lot of money…” We’re laughing about the very different directions life could have taken for both these men when McCabe cuts through it. “But that’s what I’m saying, imagine if that had happened? It’s like Martin Amis said, ‘fiction is an opportunity to live life twice’”.

Jordan isn’t just a powerful writer and strong visualist, after more than a dozen films he is one of the finest ‘actors’ directors working. How does he draw such strong performances from his cast, and his actresses in particular? He takes the compliment with a nod and says, “I don’t know how other directors work, because I’ve never seen another director working. Its one thing you never get to do when you make films, you don’t get to see how anyone else does them. I know Mike Leigh doesn’t have a script and I know, well I dunno, you know, other people go through long periods of improvisation and workshops but I don’t do any of that really. I just cast people who will approach the part from the inside and who will explore the character with me. Some of that comes from the fact that I have generally either written or co-written the script, so I look for an actor who will basically go on a journey with me and approach what they do from terms of character and nothing else”. Murphy gives an extraordinary performance in the film; delicate and sympathetic without being overly sentimental or schmaltzy. In his best role yet, he is camp and funny and rebellious, but it’s obvious from the first time we meet him that Kitten’s fabulous extrovert exterior is masking some serious emotional pain. “Well”, Jordan explains, “shortly after we’d written the script, I did tests with about ten young Irish actors, and for Cillian, well, you were there Pat”. McCabe nods his head emphatically in agreement as Jordan continues; “At the time I didn’t know if the part was playable as we’d written it. If someone was to do it very camp, very outrageous, I wasn’t going to be interested in that, like Cage Aux Folles or that remake they did in Miami with Robin Williams, The Birdcage. If it would have been like that I wouldn’t have been interested. But the first time we met him, Cillian gave this performance that really came from the inside. It wasn’t about the fact that he was wearing a purple feather boa or had a bit of blusher on his face, it was about a boy. He made it very emotional and very real and that’s when I thought that if I was to make the movie, Cillian should do it. It goes back to what I was saying earlier. He approached it solely from the point of view of character. With Cillian playing him, Kitten became almost real; it was as if the character drove the movie forward. So unique and so special, and so recognisable in a strange way”.

It’s a performance that is just starting to get recognition from Murphy’s peers, with his indelible flounce adding to his already sturdy international reputation and, more specifically, building significant noise on this year’s awards buzz grapevine, recently garnering a Golden Globe nomination for the 29 year old Corkman, a high-profile nod that is seen as a precursor to the Oscar nominations, even if only because the movie websites keep saying it. Jordan expands on his star. “Kitten displays all his nobility through remaining an individual. It’s about the struggle is to survive, to keep his soul intact. Isn’t it? To keep his innocence, to be kind. Every circumstance Kitten confronts in the movie would convince him not to be kind, wouldn’t it? He refuses to let that happen, and that’s what the triumph of the film is, really. He even refuses to hate his father, despite what he has done to him, which makes him really interesting”.

Jordan has predicted my next question, but this is the most he’s said for quite a few minutes, and the clock is ticking, so I’m reluctant to interrupt. “Ultimately”, he continues, “everybody in the movie, no matter how awful their journey or how badly they have behaved, arrives at a kind of peace. They become good”. He looks across at McCabe. “We should have called it How To Be Good”. He turns to look directly at me. “But, isn’t that the interesting thing? One of the first things Pat did when he wrote the first draft of the script, from the book, was he brought Fr Bernard back and made him have a change of heart. I saw that and thought it was very interesting. You’ve got a priest, who hasn’t raped his housekeeper as the child imagines, but he has had a relationship with her and they had a child together and, eventually, he returns at the end and has this total change of heart. So that’s one thing, right. But the other thing is, that in order to complete that change of heart, he has to be rejected by the society that made him what he is. So in order to become what a priest should be, he has to stop being a priest. To me, that’s very true of Irish life. I know everyone’s always banging on about the church and whatever, but that situation was created by the culture here. Liam’s character, Fr. Brendan, as soon as he takes Kitten and Ruth Negga’s character Charlie into his parochial house, it’s burned to the ground by his own congregation. And that would have happened, or worse. But this is a film about the past. Definitely about the past”.

I ask both men, about the same age and from similar backgrounds if they have made peace with growing up in the slate-grey Ireland of the 1970s. “The film is about a world where the only escape was England, you know”, says Jordan. “The only escape from that severe insistence that you be Irish and Catholic and whatever, unemployed generally and grim and depressed. I remember that very well, London was the great escape for people of my generation. Everybody went”. McCabe interrupts. “It’s what I call Stonewall Ireland. You know, the Sawdoctors”. Er, what? “Hmm” says Jordan. “Yeah, but if you look at Charlie, Ruth Negga’s character. She’s pregnant and unmarried. She needs either of two things; an abortion or healthcare in a hospital, yeah? She has to go to England in order to have that choice to make that. Now in our movie, she chooses to have the child, but she could just as easily have had an abortion. But she has the child in an NHS hospital. She wouldn’t have had that opportunity in the town she comes from. If even if she was sent to Dublin, the child might have ended up in a home. So, this film is a portrait of a society that was deeply unfunctional. Is that a word? Dysfunctional? Whatever. It did not function”. I make the point that Charlie’s fictional child would be my age now and how London is no longer the only answer for Irish people in their early twenties. “Oh yes”, Jordan says, slapping the table, “the country has changed, for the better. No doubt about that”. “Oh yeah”, says McCabe, “no doubt about that”.

Music, specifically bright, sad teenage pop from the era, is central to Breakfast on Pluto. The title itself comes from a song by Don Partridge, a one-man-band folk singer who still goes by the moniker ‘King of the London Buskers’. The Glam Rock era isn’t just channelled through the bubblegum soundtrack though, Roxy Music singer Bryan Ferry is cast as a sinister spiv and the hilariously glam showband that Kitten joins for a while is led by former Virgin Prune Gavin Friday. I ask both writers how the soundtrack and the film’s practical music scenes came about. “There was one song I would have loved to have in it, but we couldn’t get it or it was forgotten or something”, says McCabe. “Oh yeah”, says Jordan, “what was that?” ‘Which Way are you Going, Billy?’ by the Poppy Family. “But the book was written with loads of songs in it, wasn’t it?” says Jordan. “Oh yeah”, says McCabe, “sure you could see the whole world through songs”. “Wasn’t Honey in the book, and Sugar Baby Love and Don Partridge, obviously?” says Jordan, tapping on the table. “Yeah, yeah”, McCabe replies, more than a little wistfully. “But when we were listening to music back then and hearing about these things called niteclubs, we were just dreaming about women” says Jordan. “Yup”, says McCabe, emphatically. “It was all about women. Sex! Or the prospect of it”. Jordan jumps in, saying he remembers “sitting in a squat in North London and hearing that Peter Green from Fleetwood Mac had had a bad trip and wasn’t ever going to recover”. McCabe claps his hands with delight in the shared memory. “I remember this. He was dragged away by his nails that night shouting ‘a coalman’s life is the one for me!’ over and over again. Thrown into a van he was. He played in the Hillgrove Hotel in Monaghan two years ago there, and I went along to see him”. “You did not”, says Jordan. “I did, and he was very good”. But Kitten could have become a casualty too, I say, trying to bring the conversation back from the mists of half-remembered rockers and bad drugs. “But he did become a casualty, didn’t he, says Jordan, gently. “Becoming a rent boy and all that”. And he adds a coda in a breathlessly coquettish tone, “but he survives, you know."